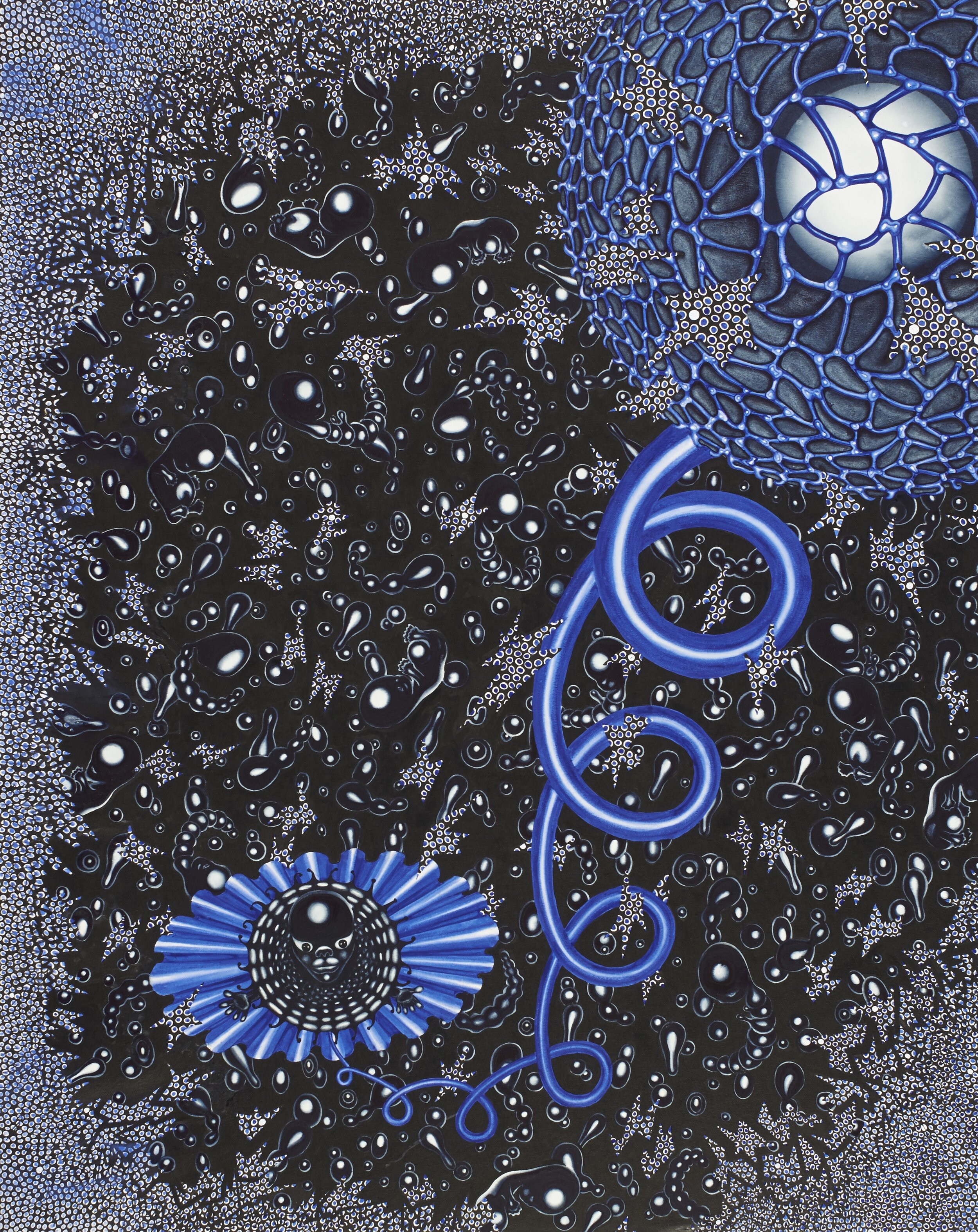

The Peach, 1981 Gouache and ink on paper. 11 x 11”

CHING HO CHENG

1946 – 1989

Infinity in a Peach Pit: My Brother’s Quest for the Eternal

Ching Ho Cheng was born in 1946 into a distinguished family of Chinese government officials. His father, Paifong Robert Cheng, served as a diplomat representing the Republic of China in Havana during the 1940s, while his mother, Rosita Yufan Cheng, worked as a fashion designer. Ching’s great aunt, Soumay Cheng—known internationally as Madame Wei Tao Ming—was a pivotal figure in modern Chinese history, credited with preventing China’s sacred province of Shandong from being relinquished during the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

The political upheaval that followed the rise of Mao Zedong made returning to China impossible for the Cheng family. When they arrived in the United States in 1950, Ching was among only 105 Chinese immigrants admitted that year under the restrictive Magnuson Act (1943–1965). As a result, the generation of Chinese American artists to which he belonged remains strikingly underrepresented in American cultural archives.

Although “Ching Ho” was his given name, he was known simply as Ching. Growing up in Queens, he quickly revealed an exceptional gift for art. In junior high school he won his first competition—a portrait of his sister Sybao—which earned him the front page of the Long Island Press. Summers at the Art Students League followed, eventually leading him to the Cooper Union School of Art.

Ching came of age during the turbulence of the Vietnam War. The massive anti-war protest of 1967 at the Lincoln Memorial—where more than 100,000 demonstrators gathered—became a turning point for him. During this period, he found solace in Taoism, which opened his perception toward metaphysical realms and became a subtle, enduring presence throughout his entire artistic practice.

During the 1960s, Ching lived in the East Village amid the counterculture movement, and later in Soho during its emergence as an artistic hub. His final and most formative home was the Chelsea Hotel, where the legendary manager Stanley Bard frequently relocated him to larger studios to accommodate his expanding canvases—often allowing late rent in the spirit of supporting artists. Ching’s discipline was unwavering; he once spent a winter painting seven hours a day in an unheated Soho loft, wearing fingerless gloves. Painting was not merely a vocation for him—it was the center of his life.

In the creative crucible of downtown New York, he forged close friendships with avant-garde artists and international thinkers who gathered at Max’s Kansas City and the Chelsea Hotel—fertile ground where bold ideas and collaborations took shape. He moved easily within the circles of the Warhol Factory, the Living Theatre, and the era’s underground performers, reflecting both his curiosity and his deep attunement to the experimental spirit of the time.

Ching worked primarily on paper, developing four distinct bodies of work: the Psychedelics, Gouache Works, Torn Works, and Alchemical Works. Although each appears visually distinct, all four are connected by a continuous metaphysical and philosophical inquiry.

His first major body, the Psychedelic series, emerged after Cooper Union. Executed in gouache and ink, these works draw heavily from Tibetan spiritual symbolism. In X Triptych (1970), the mandala structure of Panel II contains eight rings, each representing one of Ching’s guiding principles. The blue cord in Panel III extends to an astral baby—the “cord,” a concept that recurs in Glossolalia, Angel Head, and other works, symbolizing the tether between the physical body and the metaphysical plane. In “Chemical Garden,” the paisley form—an ancient icon of fertility and eternity—signals Ching’s ongoing quest to depict the essence of life. Each series culminated in a “master painting,” a summation of his exploration; for the Psychedelics, this was The Astral Theatre.

X Triptych, 1970 Panel II Gouache and ink on rag board. 30 x 30”

X Triptych, 1970 Panel III Gouache and ink on rag board. 30 x 24”

Seeking a visual language “without explosions,” Ching shifted dramatically into his second phase: the Gouache Works. Inspired by the restraint he admired in Picasso’s Bull, these paintings distilled his vision into luminous still lifes—a peach, a match, a light bulb, a palmetto leaf. Each object carries metaphysical resonance: the peach as a Chinese emblem of longevity, the palmetto as a symbol of peace and eternal life, and light as a universal signifier of hope. The culmination of this period was a work reduced to a shadow or radiant white light, a quiet transcendence that conveyed an almost spiritual purity. This element I can only describe as peace.

Untitled, 1980 Window Series Gouache on rag board. 30 x 28”

Ching’s perfectionism led to the emergence of his third body of work. He rarely kept pieces that did not meet his standards; instead, he tore them apart. Witnessing this destruction was shocking, but it became a generative act, giving rise to the Torn Works. These compositions, bold and abstract, incorporate forms such as the vortex, rectangle, and UFO disc—symbols of transcendental energy. Ching visited sites like Stonehenge, the Mayan ruins, and the Egyptian pyramids, believing they contained vortexes capable of healing or awakening higher consciousness.

During the 1980s, as Ching lost many close friends to the AIDS crisis, he turned to psychic readings with Frank Andrews. Andrews spoke to him of the “certainty of blue”—which Ching interpreted as blue for spirit and serenity, and green for rebirth. These colors entered the Torn Works, with the white torn shapes functioning as portals into other dimensions. The recurring rectangular form also echoes the monolith of 2001: A Space Odyssey—a film that profoundly moved Ching and influenced his visual lexicon.

Certainty of Blue, 1985 Charcoal, pastel and graphite on paper. 50 x 38”

Untitled, 1984 Torn Works Series Charcoal, pastel and graphite on paper. 42 x 50”

His final series, the Alchemical Works, began after a trip to Turkey in 1981, where he discovered the country’s ancient grottos. Captivated by their natural beauty and endurance, he sought to recreate their textures in his art. Using iron and copper oxide with gesso on paper, Ching developed a process in his Chelsea Hotel studio that involved soaking the works in a specially built pool to create rusted, sculptural surfaces. These “alchemical” transformations produced deeply tactile, three-dimensional forms. The series culminated in The Grotto—a monumental arc ten feet high and twenty-five feet long. This was to be his final master work and the culmination of a lifetime of seeking what he called “intimations of the miraculous.”

Across his brief yet impactful career, Ching Ho Cheng forged a singular pathway that fused spiritual inquiry, technical mastery, and a profound sensitivity to materials. Poet David Rattray described him as “a sage”—an artist whose vision was ahead of his time. Today, his oeuvre stands as an essential and underrecognized chapter in both Asian American art history and the cultural history of downtown New York.

Ching Ho Cheng viewing his Grotto at the NYU Grey Art Gallery, 1987. 10 x 25”

Sybao Cheng-Wilson